For one month in Greenland, our most important scientific instrument was a paint brush.

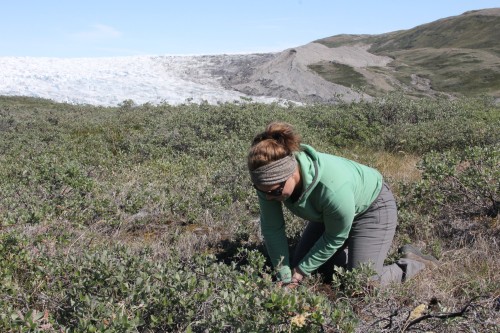

With our brushes loaded with pollen, we brushed the stigmas of hundreds of flowers, essentially acting as human pollinators. I am using this pollen-supplementation experiment to figure out if flowers could produce more seeds if there were more insects visiting flowers.

One flower we are studying is Dryas integrifolia, which is a butter-colored flower in the rose family (Rosaceae). It blooms early in the season, which is important for early emerging insects that are potential pollinators, including flies, bees, and yes, even mosquitoes.

Once we were done painting, we waited for the flowers to close up and produce seeds. Dryas seeds are wind-dispersed, like dandelion seeds. So there was a narrow window of time in which we could collect the seeds before they flew away!

If Dryas produces seeds, it creates little twirls that remind us of unicorn horns or troll hair (right). If the stem aborts, it creates little white tufts (left).

Great news: today we successfully collected the last of the seeds! Other news: now I have thousands of seeds to count! [ Volunteers welcome 🙂 ]